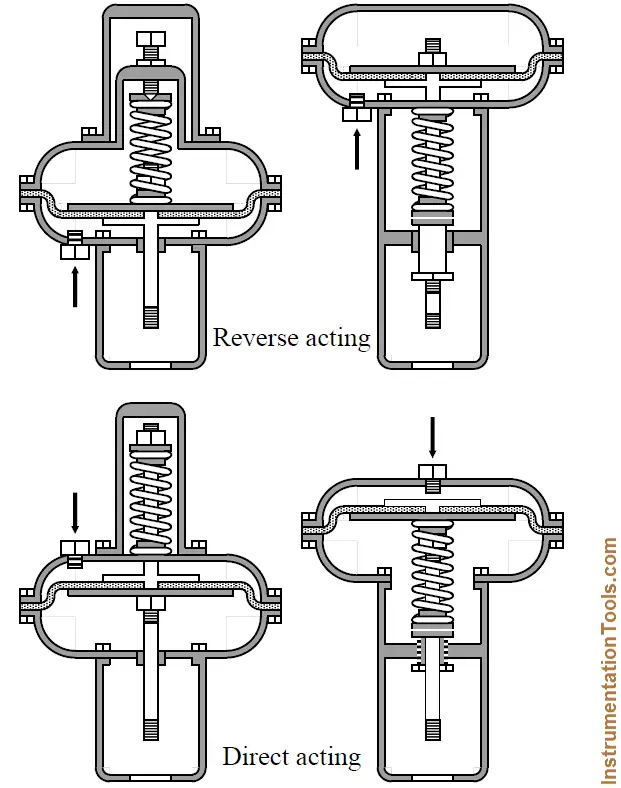

Actuators may be categorized as ‘direct acting’ or ‘reverse acting’ and some configurations are indicated in Below Figure.

In a reverse acting actuator an increase in the pneumatic pressure applied to the diaphragm lifts the valve stem (in a normally seated valve this will open the valve and is called ‘air to open’).

In a direct acting actuator, an increase in the pneumatic pressure applied to the diaphragm extends the valve stem (for a normally seated valve this will close the valve and is called ‘air to close’).

The choice of valve action is dictated by safety considerations. In one case it may be desirable to have the valve fail fully open when the pneumatic supply fails. In another application it may be considered better if the valve fails fully shut.

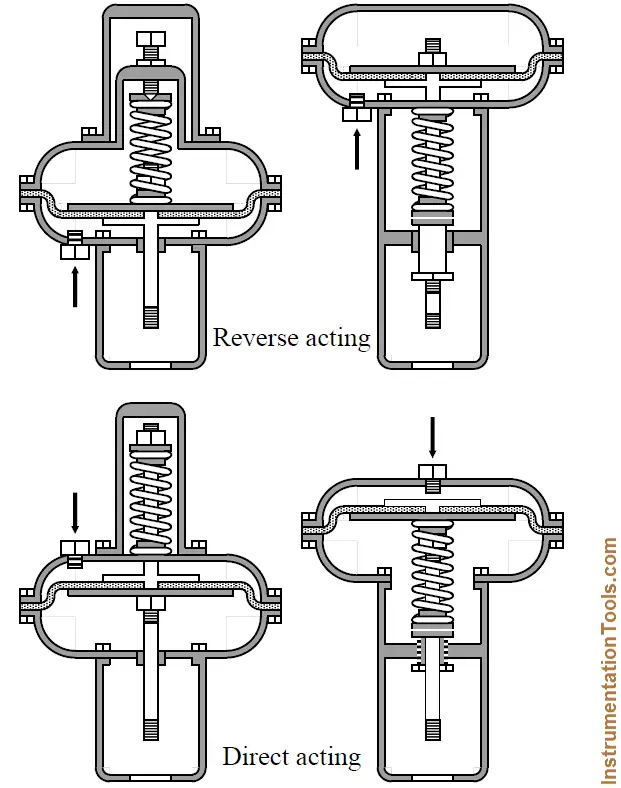

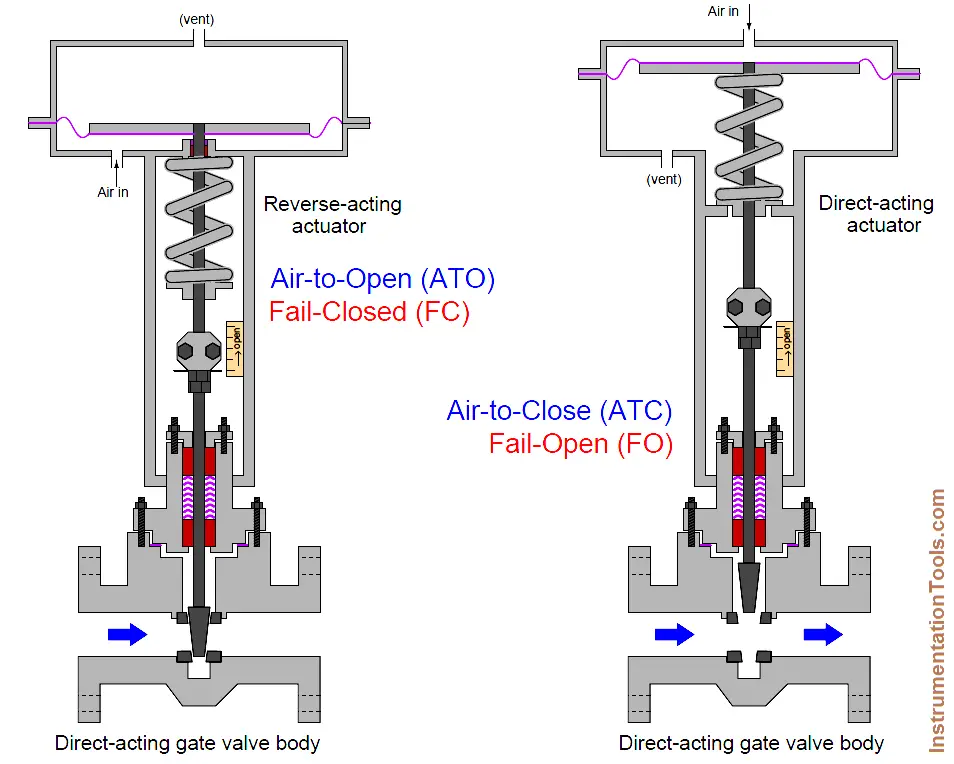

The fail-safe mode of a pneumatic/spring valve is a function of both the actuator’s action and the valve body’s action.

For sliding-stem valves, a direct-acting actuator pushes down on the stem with increasing pressure while a reverse-acting actuator pulls up on the stem with increasing pressure.

Sliding-stem valve bodies are classified as direct-acting if they open up when the stem is lifted, and classified as reverse-acting if they shut off (close) when the stem is lifted.

Thus, a sliding-stem, pneumatically actuated control valve may be made air-to-open or air-to-close simply by matching the appropriate actuator and body types.

The most common combinations mix a direct-acting valve body with either a reverse – or direct acting valve actuator, as shown in this illustration:

Reverse-acting valve bodies may also be used, with opposite results:

The reverse-acting gate valve body shown in the left-hand illustration is open, with fluid flowing around the stem while the wide plug sits well below the seat area.

Reverse-acting valve bodies tend to be more complex in construction than direct-acting valve bodies, and so they are less common in control valve applications.